The dhobi or parit in Marathi is one of the oldest communities of washer men in India. It is said that it was a dhobi who was responsible for the events of the latter half of the Ramayana. A dhobi used to be one of the twelve trades (balutedars) in any village. The washer man used to go to each house to collect dirty laundry and tying them in a large cloth he would load it onto his donkey and go to the river or any water body in the village to wash the clothes.

One would never find a dhobi in one place, maybe that’s why the saying goes that ‘a washer man belongs neither to his house nor to the riverside. Some people also say, ‘dhobi’s dog’, but I have always wondered why a washerman would need a dog? Surely his donkey is more useful to him for carrying his loads. Maybe a dog could have been useful to look after the clothes while they dried.

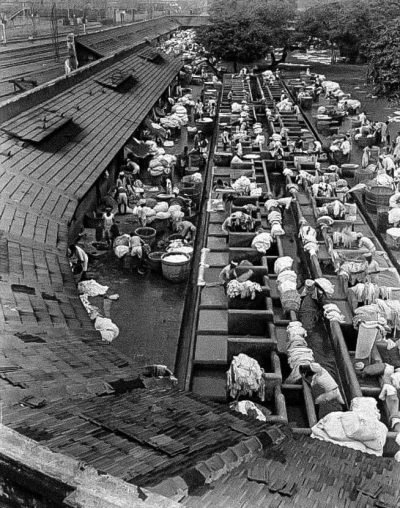

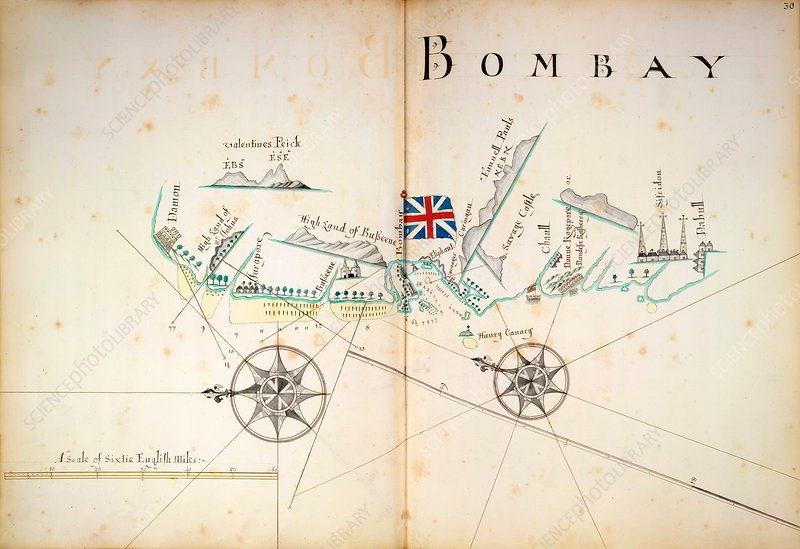

In olden days, even a city like Mumbai had a lake for washer men which went by the name of ‘dhobi talav’. In later years, it was filled up. There is a dhobi wadi in Girgaon’s Thakurdwar area where once upon time washer men lived. Even today a Dhobi ghat exists at Mahalaxmi. Since the last century, with education came a change in lifestyle, and the way people dressed changed too. Dhotis slowly went out of fashion. All educated Indian men started wearing ironed trousers. Slippers went out of fashion and shoes and socks took their place. Khaki coloured shorts too became popular. During World War II, folding one’s trousers at the ankle was no longer considered fashionable. Bush coats and Manila shirts became fashionable. Some years later, Safari suits came into vogue. Rajesh Khanna made the ‘Guru shirt’ extremely popular. These days, denim jeans are the trend.

Up to 30 or 40 years ago, almost all households had ‘Rama’ servants or a maid to wash the utensils. But people mostly washed their clothes by themselves. It was an everyday task for women to cook in the mornings and wash the clothes before the sun came up. Even though some households had servants for every chore, no one gave women’s clothes to male servants to wash. After taking a bath, the women washed their own clothes and hung them out to dry.

Before washing machines came into use, there was a particular way of washing clothes. There used to be a big, broad, rough-textured stone in the bathroom or near the water tank in the courtyard. The wet cloth was spread on this stone and washed with ‘501’ brand or ‘Sunlight’ soap bar. Then the clothes were ‘beaten’ with a wooden club to remove all the dirty water from them.

After that, each garment would be wrung and then brought down with a swinging action from the back of the shoulder and beaten on the stone once again. In wrestling, there is a move where one wrestler lifts the other one off the ground and hurls him down to the ground. In Marathi this move is called ‘dhobi-pachhad’ derived from this way of washing clothes.

Once the clothes were washed properly, they were wrung and flicked before hanging them out on a rope, a wire or on the balcony railing to dry. If one did not flick them properly, the clothes would retain a lot of wrinkles when dry.

The dhobis had coal fired stoves at their homes. They would put the clothes in a huge vessel full of water and washing soda and boil them well for a couple of hours. Afterwards, they washed them with soap and thrashed them on a stone as described above. Clothes washed this way looked exceptionally clean and white. White cotton clothes were usually starched. Ironed clothes meant clothes made stiff with starch! Some people added a touch of indigo dye in the water while washing to give a bluish tinge to the clothes and also put Tinopol, a famous powder brand to give them a little shine.

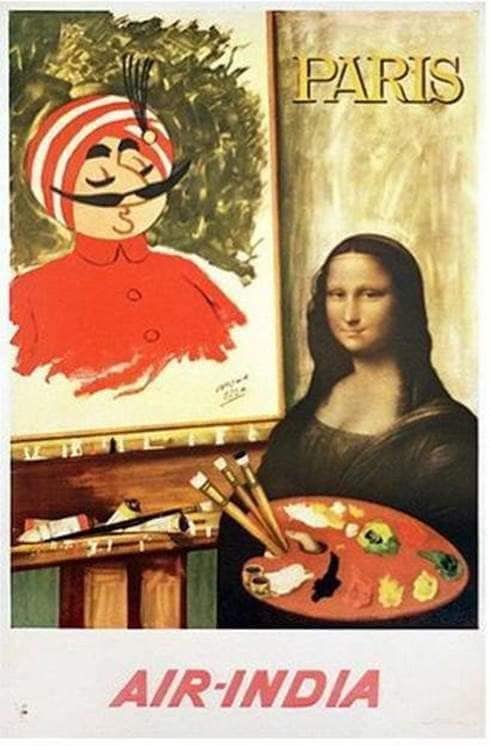

Leech and Brebourni, Band Box, and Comet were some of the expensive and prestigious laundries in Mumbai and getting your clothes laundered there was a status symbol. Band Box had around 150 branches in Mumbai, with the main office in Worli. They also had many delivery vans. Hotels, hospitals, and other Corporates gave their employees’ uniforms and other linen to such laundries to wash. Every lane in Mumbai had at least one dry cleaners’ or laundry.

In villages, bicycles eventually replaced the dhobi’s donkey. Their houses were converted into laundries. Splurging money on washing clothes in a laundry was considered fashionable. In middle class households only the clothes of the family head which he wore to office and the clothes worn only on festivals, marriages and such special occasions were given to laundries to wash. The other daily clothes of the women and children were just neatly folded and kept under the mattress for ‘ironing’!

In the washer man’s business, it is very important to be able to identify the customers’ clothes. Every laundry has its own mark or a small logo. When one gives the clothes for washing, a man behind the counter checks everything carefully with an expressionless face. He looks for stains, the laundry mark, the colour of the clothes, the customer’s initials if any, if the shirt or saree is torn, and if anything has been forgotten in the shirt or trouser pockets. Then the clothes are classified into woolen, silk and cotton piles. Only then is a receipt made.

As for the name on the receipt, a dhobi usually writes the initials which he can identify immediately. Just like a doctor’s prescription, only the dhobi himself can read what he has written on the receipt!

In the evenings, rafuwallas (darners) sat outside the laundries. They were skillful in mending clothes with small tears, or stitching patches on torn clothes. Before giving clothes for washing, the customer’s initials and the laundry’s mark were written on his clothes where it won’t be visible, like inside the shirt collar or the inside lining of trousers.

Sometimes the dhobi wrote these on a small piece of cloth and tied it to the clothes with a cotton thread. While delivering your ironed clothes, the dhobi would carefully find and take out your clothes from the shelves and would pack them neatly in a brown paper tied up with a string before handing them to you. Mothers in many households would keep that paper and string carefully for later use. The brown paper was used as notebook covers and the string was used to tie something or the other.

A lot has been written about the method of working of dabbawallas (people who deliver lunch boxes to office goers in Mumbai) and their way of marking and identifying the exact containers. But these washer men who handle hundreds and hundreds of clothes every day have remained ignored. All the dhobis wash their clothes together at the dhobi ghat, but not a single item of clothing gets misplaced. One can locate the owner of a clothing item from the specific laundry mark on it.

Many dead bodies in complicated crimes and some accused have been identified and found because of these laundry marks. The clothes that you give for washing, do get burnt occasionally, or are stained, or some items are misplaced. Clothes that are misplaced or stolen from laundries eventually end up in the Chor bazaar and are sold there.

These days, people have started washing clothes at home since everyone has a washing machine and iron. Laundries are needed only for dry cleaning silk garments. But even if people have irons at home, they do not have time to do the ironing or are just too lazy to do it by themselves. So, giving one’s clothes for ironing has become the new trend. Many laundries have had to close their shops because of this, and North Indian bhaiyyas have taken their place as dhobis who iron clothes.

These North Indian dhobis opened their small shops under staircases, in the courtyards of large housing complexes or at the corners of lanes. Just a small table, a rack to keep clothes and a coal-fired iron, occasionally a small table fan, a photo of Lord Hanuman and a small transistor radio – that was all they needed! No taxes and no bills to pay… Most of the times, the shop premises were also illegally acquired and so they didn’t have many overheads.

‘What to do, Bhabhiji, we cannot afford anything!’ was their favourite refrain to throw at anyone. And yet, they also delivered your clothes at your doorstep with a minimal fee! If no one were home, they would keep your clothes at the neighbours’ or with the society watchman!

They never kept their shop closed on any day of the week! And to add to this, they would present you their bill at the end of every month! Customers and the dhobi, both were happy with this arrangement. These bhaiyyas have brought something of a revolution in this business and changed it completely. The seemingly uneducated, harmless dhobi bhaiyya has today become an inseparable part of our daily lives!